Max Nathan (L'60), icon, scholar, friend, has died

Almost everything about Max Nathan was larger than life.

When he practiced law, he became one of the nation’s leading estate planning attorneys. As a scholar, he studied Shakespeare and founded a festival in New Orleans to honor the bard. As an educator, he went all in, teaching generations of Tulanians for more than 50 years.

Nathan (L’60), one of the members of the inaugural class of the Tulane Law School Hall of Fame, renowned attorney, scholar, father and friend, has died. He was 86.

“Max was a one-of-a-kind institution at Tulane Law School for most of his life,” said Dean David Meyer. “Over five decades on our faculty, he left an indelible imprint on generations of Tulane Law students and colleagues.”

“His razor-wit and intellect, his irrepressible zest for life, and his generous spirit helped define Tulane for a great many of us.”

His humble beginnings belied what his later life would become – vibrant, over-the-top, adventurous. He was a leading figure in Louisiana’s law of partnerships, successions, donations, and wills, and he was President of the Louisiana Law Institute from 1998 to 2001. He was one of the longest serving adjunct professors at Tulane Law, where he taught security rights and the annual summer Bar Review course for more than 40 years.

Nathan was born into a Jewish family in Shreveport during the Great Depression. During high school, he excelled in public speaking and as a member of his high school debate team, which earned him a full scholarship to Northwestern University in Illinois.

He began his legal studies at Yale Law School but, drawn home to Louisiana and his love for Newcomb student Dotty Lee Gold (NC ’59, SW ’82) of Alexandria, he transferred to Tulane where he graduated second in his class in 1960. He was a Dean’s Medal recipient and a member of the Tulane Law Review, and notably, wrote an award-winning Comment detecting a significant error in the translation of the Napoleonic code from French to English which altered the reading of judicial mortgages.

Among his friends, he counted Judge Jacques Wiener (A&S ’56, L’61), who spoke eloquently of his best friend in 2019, when Nathan was honored with the President’s Award from the Louisiana Bar Association. Nathan and Wiener, both from Shreveport, went to elementary, high school and, later, law school together.

“We have remained colleagues and friends for over 80 years,” Wiener said. “I can say unequivocally that Max Nathan is the most brilliant person I have ever known personally. Not only that, but he is also a true Renaissance man: Attorney-at-law, law professor, Shakespearean scholar, musical aficionado, parent, grandparent, and a true friend to untold hundreds.”

From law school, Nathan went on to clerk for the legendary civil-rights era Judge John Minor Wisdom (L ’29), a clerkship he described as “the most intellectually stimulating year of my life.” Nathan’s time with Wisdom, despite their political differences (Nathan was an avowed Democrat having worked on the presidential campaign of Adlai Stevenson while Wisdom was a Republican), influenced him for life.

Meanwhile, he and Dotty had four daughters they raised in New Orleans, and Nathan went on to become a founding partner of the firm of Sessions, Fishman, Nathan, and Israel in New Orleans, becoming a preeminent attorney on succession and estate planning. When Dotty passed away in the late 1980s, Max established the Jewish Endowment Foundation’s Dotty Gold Nathan Memorial Lecture Series which brought to New Orleans experts and speakers on mental health and related areas.

Later, he and Fran Swan became partners and were together for more than 30 years, continuing the charitable work he was so passionate about and becoming regulars on the local opera scene.

Nathan is credited with making Louisiana’s laws better, serving for more than 50 years in the Louisiana State Law Institute as a member, reporter, and later chair of the Committee on Successions and Donations.

Ron Scalise (L’00), the John Minor Wisdom Professor of Civil Law and a former student of Nathan’s, went on to teach the Security Rights class that the elder attorney had taught for 50 years. He recalled that Nathan was a “lawyer’s lawyer.”

“He was the best of the old-school lawyers who practiced soup to nuts,” Scalise said. “He would do cutting-edge transactional work one day and then go on to do high-level litigation the next. There are cases he litigated before the Louisiana Supreme Court that I still teach today.”

One of them, Scalise said, involved Nathan on one side of the case and the legendary Marian Mayer Berkett (L’37), one of Louisiana’s pioneering women lawyers, on the other. Berkett was inducted into the Tulane Hall of Fame in the same class as Nathan in 2013.

Scalise recalled Nathan’s generosity for students. While in law school, he sent Nathan a paper he had written, although he didn’t know the professor well.

“He not only sent it back to me with edits and suggestions, but he told me to come over to the house,” Scalise said. “And we sat, drank wine, talked about the paper. And that paper was published in the Tulane Law Review. That was how he was, just very generous with his time.”

Nathan taught at Tulane Law for more than 50 years, educating legions of students who went on to have great careers, and later have children who in turn returned to Tulane Law, only to be taught by Prof. Nathan. One of his students, Carole Cukell Neff (L’77), co-wrote with him the standard book on Louisiana estate planning which is still in use today.

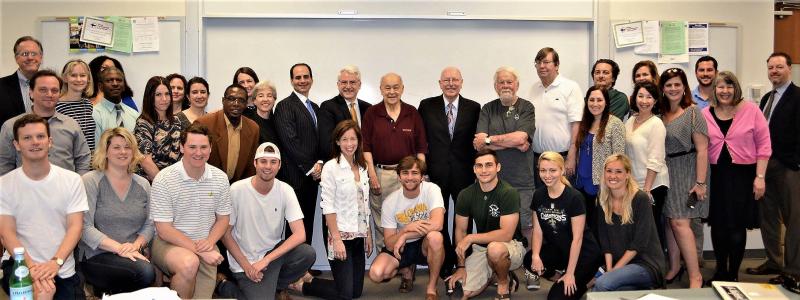

In his 50th year of teaching in 2015, the faculty surprised Nathan by entering his classroom at the conclusion of his last class to applaud him and honor the milestone. Nathan, true to form, was humbled and wondered what in the world was going on. Then, a student surprised both Nathan and the faculty by rising to present her own tribute on behalf of her classmates. Cary Phelps (L ’16) noted that her father, Ashton Phelps (L ’70), had also taken Nathan’s class decades earlier and that at least two other students in the class were also second-generation Nathan students.

“Even if you didn’t take his regular classes,” said Scalise, “every student took his Bar Review course. He taught generations of Tulane students.”

Of his love for teaching, Nathan wrote in 2015:

“I have taught part-time at Tulane Law School for 50 years, and I have often said that I consider teaching a class as exercise for my brain. For the entire hour of the class, I cannot let my mind wander even for a few seconds. And I always leave class more energized than when I began, unless I think I have made a mistake and said something that I should not have said. In order to teach a class, a teacher cannot simply stand up before the students and start talking! A teacher has to prepare for the class. I do not think I have ever studied more than in the early years of my teaching, when I studied more than ever to be prepared for the class, especially a class on a subject that I had not taught before. There is very little as rewarding as the satisfaction of closing the gap and being prepared for a class, and then the joy of actually teaching it.”

Nathan was beloved by students, both because of his professionalism, ethics, compassion, and work ethic but also because he most certainly had a sense of humor. He was a master of puns and double-entendres and wouldn’t pass on a naughty joke, friends and colleagues recalled.

“He was in law practice not to make money,” Scalise said. “He did it to help people and he did it because he loved it. That was his inspiration.”

Paul Verkuil, Dean of Tulane Law from 1978 to 1985 and a close friend of Nathan, recalled that Nathan had a significant hand in helping Verkuil recruit Professor Thanassi Yiannopoulos to join Tulane’s faculty from LSU, “a major coup for Tulane and its civil law program, achieved over trips to Baton Rouge and cocktails at Bartolus Society meetings at Antoines.”

“He was so kind, generous and intelligent, brilliant in his field,” Verkuil said. “He was always ready to help and serve Tulane, including the preparation of numerous deeds of gift drawn by him for donors of chairs and scholarships.”

Throughout his storied career, Nathan never stopped learning. Whether it was researching legal cases, learning French, writing poetry, collecting treasured art, or founding the New Orleans Shakespeare Festival, he was a light in every room, say friends and colleagues.

He was active in many philanthropic causes, serving as Chapter President of the Anti-Defamation League, establishing its Torch of Liberty Award, which he received in 1992. He also was Chair of the New Orleans chapter of the ADL. He served as past president of the Jewish Endowment Foundation, where he helped establish the creation of an Americans Holocaust Memorial Fund. He was past president of the Jewish Family Services and served on the board of the Jewish Federation of Greater New Orleans and well as the board of Temple Sinai.