Tulane study: Louisiana's severe air pollution linked to dozens of cancer cases each year

Exposure to high levels of toxic air pollution is estimated to cause 85 cancer cases per year in Louisiana, according to a Tulane Law peer-reviewed study published today in Environmental Research Letters.

The study, conducted by researchers at the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, compared neighborhood-level cancer incidence data from the Louisiana Tumor Registry with pollution-related cancer risk, as estimated by the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Air Toxics Assessment (NATA). The analysis accounted for geographic differences in other factors that are related to cancer rates, including poverty, race, occupation, obesity, and smoking.

In addition to estimating Louisiana’s cancer burden from toxic air pollution, the study revealed that poverty has an impact on the relationship between toxic air pollution and cancer incidence: the link between the two was apparent in neighborhoods with above-average poverty rates, but was not detected in more affluent communities.

“We discovered that the relationship between air pollution and neighborhood cancer rates is different in poor versus affluent neighborhoods,” said Kimberly Terrell, a Research Scientist at the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic and lead author of the report.

This is the first peer-reviewed study of Louisiana’s cancer burden to account for an interaction between poverty and pollution, Terrell said.

According to the most recent data available from the Centers for Disease Control, Louisiana has the second highest rate of new cancer cases in the nation. While the State of Louisiana funds a cancer prevention program, it does not yet identify pollution exposure as a cancer risk factor.

The Tulane study found that among neighborhoods with above-average poverty rates, higher levels of toxic air pollution were strongly linked to higher cancer rates, Louisiana neighborhoods with above-average poverty rates and the most toxic air (i.e. top quartile) had an average annual cancer rate of 502 cases per 100,000 people. This cancer rate was significantly elevated compared to corresponding neighborhoods with low levels of toxic air pollution (bottom quartile; 478.8 cases per 100,000 people) and compared to the overall state average (480.3 cases per 100,000 people). These respective differences account for 91.8 extra cancer cases per year or 85.8 extra cancer cases per year, respectively, after taking into account the population size of the affected neighborhoods (400,788 people).

By contrast, the study did not find a link between air pollution and cancer for more affluent neighborhoods. According to the study authors, these contrasting results could mean that impoverished communities are more susceptible to pollution, or, alternately, that the link between pollution and cancer is harder to detect in affluent communities because affluent people tend to relocate more often, making it harder to connect their pollution exposure with any health outcome.

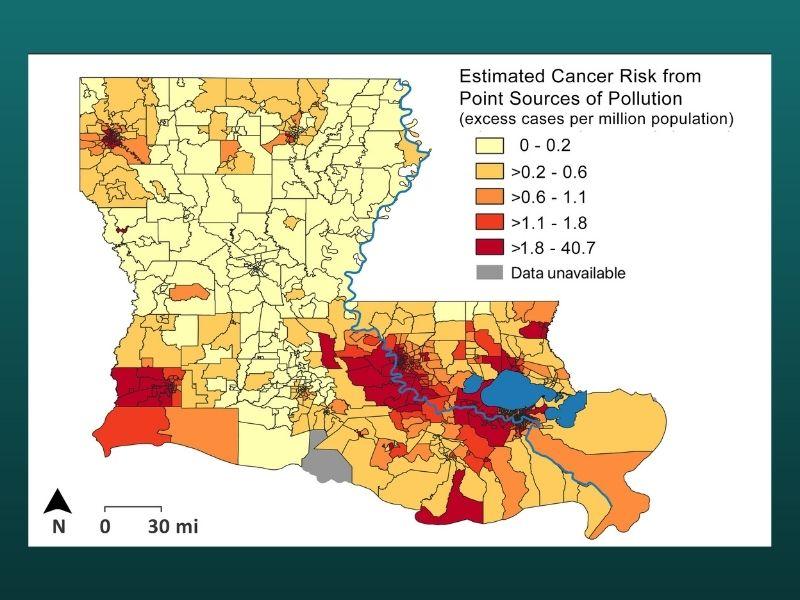

The study included neighborhoods throughout Louisiana, including the heavily industrialized area between Baton Rouge and New Orleans colloquially known as “Cancer Alley.” While toxic air pollution comes from many different sources, the study focused specifically on cancer risk from “point sources” of toxic air pollution. Point sources in this data set include industrial facilities and power plants, but do not include vehicles, wildfires, airports, homes, or other mobile or diffuse sources of pollution.

The authors accounted for the time lag between pollution exposure and cancer diagnosis by comparing the most recent cancer data available (cases diagnosed between 2008 and 2017) to historical estimates of pollution-related cancer risk, reflecting pollution levels in 2005. Because the study used publicly available data from state and federal agencies, the authors’ findings can be independently reproduced.

Gianna St. Julien, a co-author of the report and a Clinical Research Coordinator at the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, points to the value of EPA data for cancer prevention.

“Our study connects EPA’s estimates with actual cancer cases in Louisiana. The findings provide evidence that many cancer cases in Louisiana could be prevented by reducing pollution in neighborhoods where EPA estimates a high cancer risk.”

“This study underscores the need for robust environmental regulations and legal frameworks to protect vulnerable communities. Learn how to combat environmental challenges with Tulane's online Environmental Law program.

The full study is available here.